News

The crisis in Sudan, explained

One year into a conflict, nearly half of the country’s population require some form of humanitarian assistance and the situation shows no signs of improving.

Read MoreThis article was last updated on October 29, 2024

A little over a year into the conflict in Sudan has created, among other things, what is now the world’s largest hunger crisis.

Over 21 million people (nearly half the country’s population) are facing high levels of food insecurity according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). On August 1, 2024, the IPC’s Famine Review Committee confirmed that a man-made famine has taken hold within Zamzam camp. One of North Darfur’s largest displacement sites, Zamzam is home to over half a million people fleeing violence who are now unable to leave, farm, or afford the food staples and other commodities that are available to them in the area.

Read on for what that means, how we got here, and everything else you need to know about the current hunger crisis in Sudan.

As reported earlier this summer, Sudan “is facing the worst levels of acute food insecurity ever recorded by the IPC in the country.” When the IPC declared famine in August, hunger levels in the country were especially high as it was in the middle of the lean lean season between harvests. The famine-monitoring network estimated then that conditions would continue into the end of October (at the end of the lean season).

However, that doesn’t mean that we’re past the worst of the crisis. Indeed, the IPC initially said that the likelihood of the famine continuing into the new year was “high,” and has since added that “the likelihood of famine remains high in Zamzam camp after October and that many other areas throughout Sudan remain at risk of famine as long as the conflict and limited humanitarian access continue.”

The current IPC projections will take us through February, 2025, and estimate that 21 million people are facing high levels of acute food insecurity. This includes nearly 109,000 facing famine conditions (IPC Phase 5), with 6.38 million facing emergency levels (Phase 4) and nearly 14.6 million facing crisis levels of hunger (Phase 3). Together, this accounts for 45% of the country’s population, and an additional 37% (roughly 17.5 million people) are facing a slighter — but still significant — level of food insecurity.

The most extreme levels of hunger are concentrated in all five states of Greater Darfur, as well as South and North Kordofan, Blue Nile, Al Jazirah, and Khartoum.

“People are having to eat leaves and mud for energy just to try to survive,” says Concern Sudan country director, Dr. Farooq Khan of the current situation. “The suffering is so egregious they don’t even have the energy to shout aloud or ask for help anymore.”

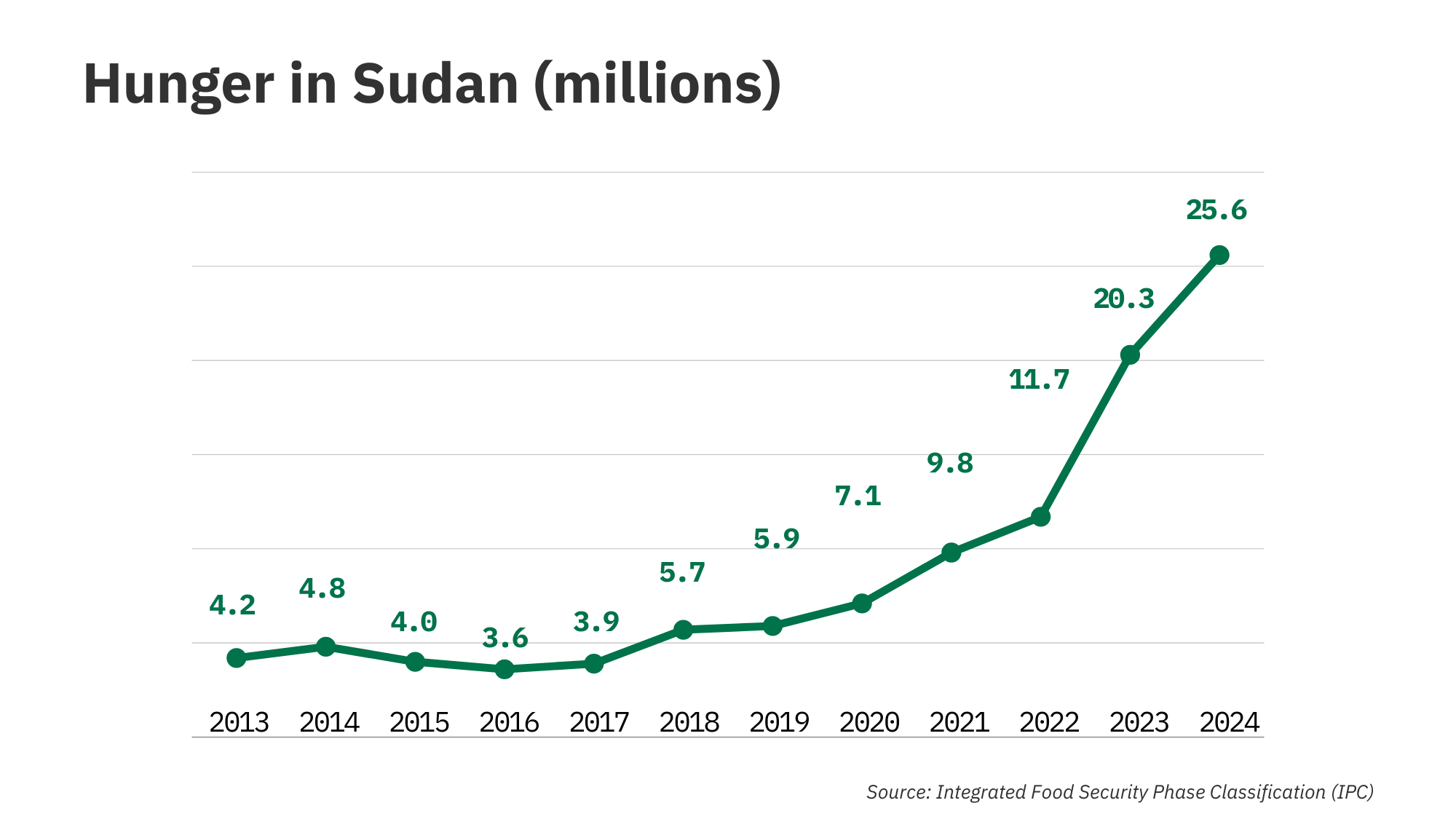

Hunger was an issue in Sudan even before conflict broke out in April, 2023. At the end of 2019, approximately 5.9 million Sudanese were facing chronic hunger. An estimated 80% of all stunted children lived in just 14 countries. This included Sudan, where extreme poverty, inadequate feeding practices, and the effects of climate change were key drivers for high malnutrition rates, leaving just over 14% of all Sudanese children under the age of five acutely malnourished.

The knock-on effects of the early years of the pandemic didn’t help matters. Border closures affected the supply chains for staples like wheat and vegetable oil, a problem for a country that relies on imports for roughly 25% of its essential food supplies. Emergency supplies were quickly depleted, and many of the most vulnerable Sudanese lost or saw drastic reductions to their incomes and livelihoods as a result of closures and inflation. The situation worsened in 2022, following the invasion of Ukraine (Sudan relied on both Russia and Ukraine for some of its essentials, including wheat).

At the end of 2022, one year into a shift in political leadership and amid ongoing instability and uncertainty, the IPC estimated that as many as 11.7 million people were facing food insecurity. This represented a nearly 100% increase in hunger levels pre-pandemic, and a 225% increase compared to 2016, which had the lowest levels of recorded food insecurity in Sudan over the last decade.

The crisis in Sudan escalated on April 15, 2023, with violent clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in the capital of Khartoum sparking a nationwide conflict and massive displacement, both within Sudan and in neighboring Chad.

For those who have remained in Sudan, food shortages have become a fact of life. The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that food production fell by 46% in the first year of the conflict as people were driven from their homes or unable to safely work their farms (agriculture accounts for 80% of employment in Sudan). Food processing factories ceased operations due to the war, and the only factory in the country that produced lifesaving ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), the standard treatment for childhood malnutrition, was destroyed.

Fighting has been especially intense in Darfur and Al Jazirah, the region known as Sudan’s bread basket. Adding insult to injury, forecasts for 2024 suggest that the rainfall will be below-average this year in the country, further impacting crops, livestock, and the availability of water. Humanitarian access has also been limited by violence.

The World Food Program warns that Sudan is unable to afford to import enough food to cover the shortage due to hyperinflation, and we are now seeing that play out in the country’s lean season, which began in May and is expected to continue through September. What food is available in the country is likewise too expensive for many of the most vulnerable Sudanese families (particularly those displaced by conflict). In its analysis of Zamzam camp, the IPC noted that the camp’s main market was functioning intermittently, with irregular deliveries made at high risk to those carrying them through unsafe areas. This has contributed to the price spikes of available goods.

“People are selling off their assets to buy food for their families. Supplies to commercial markets have been disrupted by the fighting. Many people are now totally reliant on aid in order to have just one meal a day,” explains Concern Sudan country director, Dr. Farooq Khan.

Food security is a key focus in mitigating the effects of the conflict in Sudan. However, this is just one piece of the puzzle. Healthcare facilities have also faced attacks in the last 15 months. As malnutrition rates continue to rise, this means that many Sudanese (especially children) will face an additional challenge: receiving adequate medical care.

“We continue to face challenges in the movement of goods and staff into and across the country,” says Amina Abdulla, Concern’s regional director for Horn of Africa. “It is only a matter of time before we run out of supplies in the various health facilities that we support and services come to a halt despite the ever-increasing levels of needs across the country.”

“The 90 clinics we are supporting are under stress,” adds Dr. Khan.

In a world overrun by conflict and crisis, humanitarian agencies are wary of making hyperbolic statements. However, in a March 20, 2024 speech to the Security Council, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Edem Wosornu warned of “a far-reaching and fast-deteriorating situation of food insecurity in Sudan.” At the one-year mark for the conflict, 18 million people were facing high levels (Crisis-, Emergency-, or Catastrophe-level) of food insecurity.

Just three months later, those projected insecurity rates have risen by more than 40%. Dr. Khan says that even this may be a conservative estimate: “From the feedback we are receiving, the IPC could be under-reporting the situation by 5-10%.” Regardless of the label we give it, however, the net effect is the same: Over three-quarters of a million people, if not more, will face extreme food shortages, which will result in heightened fatalities (especially for children).

“Many people are now totally reliant on aid in order to have just one meal a day.”

Since famine was confirmed in August, Sudanese authorities reopened a critical crossing between Sudan and Chad in Adre, the shortest and most effective route for getting humanitarian assistance into the country according to the WFP. The first crossings in six months took place in late August, and the crossing will be open through the end of November.

The reopening made it possible to deliver larger quantities of critical humanitarian aid to western Sudan, and in the first ten days alone 59 trucks carrying medical, food, shelter, and other essential items crossed the humanitarian corridor, reaching nearly 195,000 people. However, this is a drop in the bucket compared to the roughly 36 million people in the region (including neighboring Chad and South Sudan) who require food and nutritional support.

Further complicating matters, heavy rains, flooding, and ongoing insecurity in September and October have delayed the movement of vital aid and made clinics and distribution points harder to access. The rains also fueled rising cases of malaria and cholera.

“This is the world’s largest humanitarian crisis which is continuing to deteriorate each day,” says Dr. Khan. “A major response by the international community is needed to make the warring parties provide access to humanitarian organizations, across national borders and military frontlines.” Dr. Khan adds that funding continues to be a major barrier to effectively delivering aid and avoiding a major humanitarian catastrophe: As of September, just 41% of the required funds for baseline aid in 2024 had been provided.

At the moment, the two biggest challenges to the hunger crisis in Sudan are political and financial. However, that doesn’t mean the situation is hopeless.

The IPC estimates that conditions will continue in Zamzam and the surrounding area (El Fasher), with trade flows and humanitarian access severely interrupted through at least January 2025. While the rainy season begins in October and may make foraging for wild foods a bit easier, this will leave people vulnerable to attacks and ongoing violence. The start of the rainy season will also accelerate waterborne and vector illnesses, exacerbated by overcrowding in the area, a lack of health services, and poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure.

Concern has warned of a spiraling hunger crisis in Sudan since war erupted in April, 2023. We are now calling on UN member states, especially those on the Security Council and with the greatest influence in the region, to use their power in calling for an immediate ceasefire and safe access for humanitarian organizations to reach civilian communities in need of assistance. “Accessibility to impacted communities and an uninterrupted supply of essential health and nutrition commodities are our key issues at this stage, if widespread famine is to be prevented and lives saved,” says Dr. Khan.

“Nobody should die of hunger due to a lack of funding, while waiting for peace.“ — Dr. Farooq Khan, Country Director, Concern Sudan

“Accessibility to impacted communities and an uninterrupted supply of essential health and nutrition commodities are our key issues at this stage, if widespread famine is to be prevented and lives saved,” says Dr. Khan.

“One thing we know about famine is that it will spread if it doesn’t receive the necessary response needed from across the international community. Otherwise, it is going to spread like wildfire.”

In 2025, Concern marks 40 years of lifesaving work in Sudan. This includes responding to the current crisis with programs including health and nutrition, livelihoods, food security, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services. In the last two years, we have been able to respond to an ever-changing situation and ensure that help is going where it’s needed most.

Last year, Concern Sudan reached nearly 484,000 people, delivering lifesaving health and nutrition support, emergency supplies, and cash transfers. Across 81 health facilities, we have treated children under the age of five for acute malnutrition. We also supported nearly 5,900 families with multipurpose cash assistance to ensure they can afford the items they need the most, at a time when needs are at an all-time high.

In Chad, our teams have been supporting displaced arrivals from Sudan with essential supplies, shelter, and health and nutrition support. We’ve treated thousands of patients in the last two years in our health and nutrition clinics, and distributed essential supplies like non-food item (NFI) and dignity kits.

Your tax-deductible donation to Concern will help us to provide even more food, water, sanitation, shelter, and financial support to those most in need.