In 2000, Community Management of Acute Malnutrition redefined how we fight hunger crises. Here's how we're building on that success to fight malnutrition before it even starts.

Mariama Badje, a 55-year-old Nigerien grandmother of 12, noticed something was off with her youngest grandchildren, Souhaibou and Misiwarou. “Both children got malaria, and then diarrhea. They were both losing weight; they lost their appetite,” she says.

The twins’ father had passed away when they were only three months old. Their mother also hadn’t been able to produce enough breastmilk for both babies. Fortunately, their grandmother was a community health volunteer and knew what to do. Mariama measured the babies’ mid-upper-arm circumference (MUAC). When the measurements fell within the range of acute malnutrition, she brought them both to the local health center, supported by Concern.

“We got some emergency food for the children. They continued taking the food and a lot of water and they started getting better. And because I followed the instructions from the clinic, the children quickly recovered,” she says. After just two weeks, they showed marked improvement.

Working towards prevention

Mariama’s story is one of millions that we’ve seen over nearly 25 years of Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), the standard-setting treatment for hunger among children under the age of five. In that time, thousands (if not millions) of community volunteers like Mariama have helped to screen their friends and neighbors’ children for malnutrition, and local centers have been able to provide shelf-stable therapeutic food to help the majority of patients recover.

Still, CMAM is a reactive program. It responds to hunger crises that are already underway. And we can only get so close to ending hunger in this manner. “We can throw money at treatments forever, but it’s not always a good return on investment,” says Katie Waller, Concern’s Director of Strategic Partnerships. “Working towards prevention is much more cost-effective.”

And, as it turns out, as unpredictable as the world may seem, hunger emergencies — and health emergencies more broadly speaking — can often be predictable. Many countries face regular hunger seasons between harvests. Monsoon seasons mean an increase in waterborne diseases like diarrhea and cholera. One thing we confirmed early on with CMAM was that early detection of malnutrition leads to improved treatment outcomes and fewer cases of severe acute malnutrition. Given this, was it possible to apply this principle towards an even more preventative approach? Can we treat hunger and malnutrition before they even exist?

Twelve years ago, Concern tested this theory, beginning in a region that’s roughly the size of West Virginia.

An early warning system for malnutrition

Droughts in the Horn of Africa have increasingly become the rule versus the exception. In May 2011, then-president of Kenya Mwai Kibaki declared a national emergency in response to one that had begun the year before and had left over 4.25 million people in need of food assistance. This included over 300,000 children affected by acute malnutrition. Many were in the northern county of Marsabit, which was among the worst-hit areas and had malnutrition rates far exceeding the crisis threshold.

In some ways, droughts are among the best worst-case scenarios: They aren’t a sudden natural disaster, like a cyclone or a hurricane. They’re also more predictable than an earthquake. We get early warnings based on weather reports and can plan accordingly. However, many areas affected by the 2010-11 drought did not have these response methods in place, leaving local health systems to play catch-up.

Having worked in Kenya since 2002, including implementing CMAM programs, Concern began to look at the long-term weather predictions for Marsabit against the increased caseloads of malnutrition. Drawing on principles of disaster risk reduction as well as CMAM, we began to test out a model we called CMAM Surge. The goal was to help local health systems effectively manage increased caseloads of acute malnutrition when it was clear an emergency was going to hit, without undermining the health or nutrition systems already in place.

Getting ahead of the surge

Working with the Kenyan Ministry of Health, UNICEF, and local healthcare facility staff, Concern launched CMAM Surge in May 2012 across 14 clinics in three cities in Marsabit: Moyale, Chalbi, and Sololo. The initiative was part of a larger ECHO-funded project geared towards helping the two participating Sub-County Health Management Teams (SCHMTs) to strengthen their early warning/early action systems.

In some ways, the components of CMAM Surge were already there: CMAM was a known program in Marsabit, and there were organizations tracking weather patterns. Still, as Waller notes, “we never really talked about it in this way before: the link between seasonality and health, which is the link between climate and health.”

Yet this also seemed to be a key link in helping governments leverage warning signs of an imminent nutrition emergency towards early action, action that could in turn help local health facilities and teams better respond to increased demand for services.

“The link between seasonality and health…is the link between climate and health.” — Katie Waller, Director of Strategic Partnerships for Concern Worldwide

The Surge approach

CMAM Surge was built around an eight-step process to help governments and healthcare teams respond to changes in caseloads and capacity. It begins with the setup:

Step 1: Analyze trends and local contexts, including seasonal trends and known risk factors in a given area.

Step 2: Review the capacity of individual health facilities.

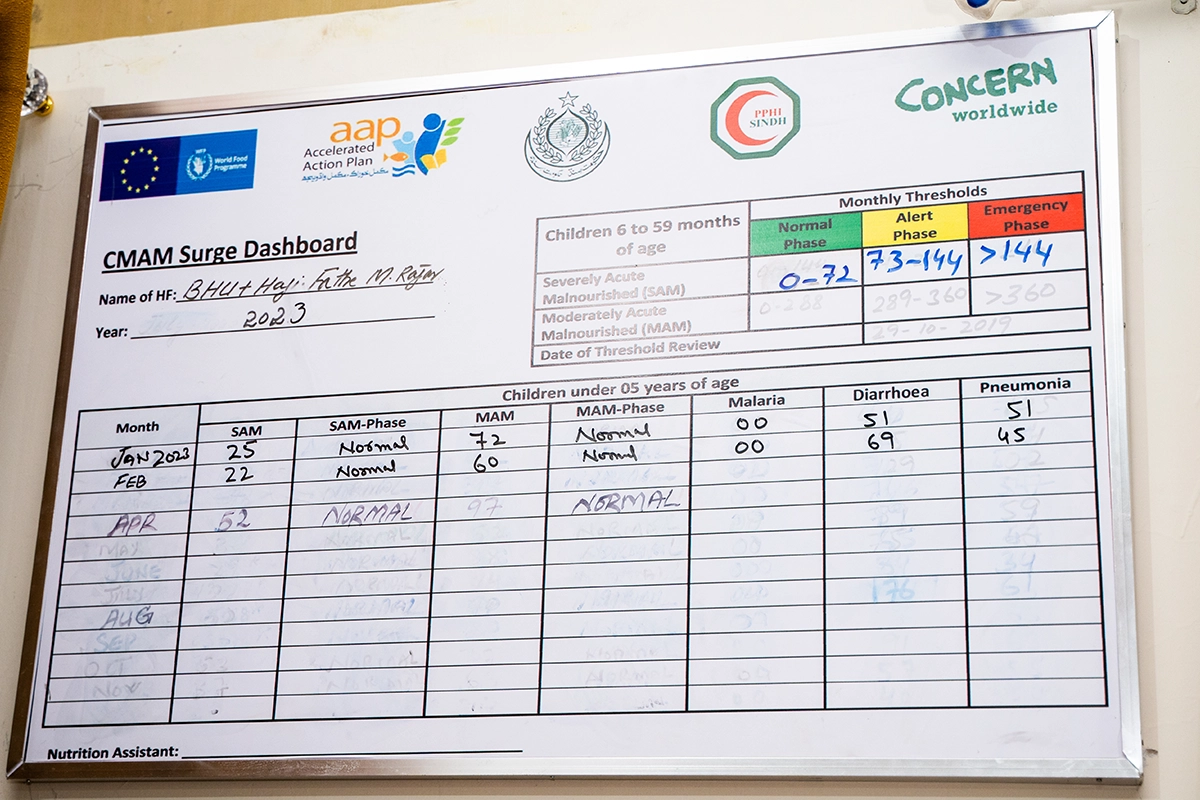

Step 3: Set thresholds specific to each facility that, when crossed, designate a shift from business as usual to an increasingly severe situation that requires greater action (these situations are phased from alert to serious to emergency levels).

Step 4: Define these greater actions that would need to be taken, and agree on both these actions and their budgets between healthcare facilities and local or national governments.

Step 5: Formalize those commitments.

Once a plan is in place, the next phase is to monitor and act.

Step 6: Healthcare facility staff monitor thresholds on a daily basis using their routine data, enabling action as soon as a threshold is crossed. The status of each health facility is also monitored at a higher level (such as the district), which in turn also monitors trends across a wider geographic area and can call for a higher-level response if needed.

Step 7: Take the agreed-upon actions to respond to the situation, scaling up and down in accordance with the severity. The first level of action is taken within the facility itself, but sometimes these action plans branch out into communities.

After an emergency subsides comes the final phase and step:

Step 8: Ongoing review, monitoring, and adaptation of Surge activities, including reviewing thresholds and responses in order to improve with each Surge.

A small detour versus changing the map

Part of the success of Surge so far has been based on the fact that it doesn’t require huge changes to be made at the clinic level. Waller points out that many healthcare facilities were already tracking many of the data points that are important for Surge tracking. “It’s a small detour versus changing the map completely,” says Waller.

The real change comes in the cohesion and increased communication between national health ministries and systems and the individual, frontline clinics. Getting ahead of the curve can be time consuming, especially when you’re doing all the running you can to keep in place, but the value of Surge, and the ability it gives frontline health workers to advocate for themselves, was proven in Nairobi during the COVID-19 pandemic, when maternal and child health priorities were met amind increasing coronavirus caseloads.

“The more we move towards prevention versus response, the more we move from treating malnutrition to preventing it,” says Waller. This process is part of what has become known among NGOs as “nexus programming,” initiatives like CMAM Surge (as well as Disaster Risk Reduction) that sit at the intersection between humanitarian aid and ongoing development, working coherently to address challenges before, during, and after an emergency.

This is also a way of addressing some of the biggest problems with traditional humanitarian aid, creating more cost-effective solutions that reach the people who need them most, while also reducing dependencies on organizations like Concern.

Beyond nutrition

A little over a decade into Surge, we’re seeing the results. Following the success of the initial pilot in Kenya, the Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition Surge toolkit was incorporated into the county-level strategic planning documents, including the County Nutrition Action Plan and the County Integrated Development Plan. Fellow organizations including Action Against Hunger, Kenya Red Cross, and International Rescue Committee have also begun to incorporate the approach into their own programs.

One thing we quickly noticed, too, was that Surge was useful in managing peaks in other common childhood illnesses, which led to a slight rebrand from CMAM Surge to the Surge Approach. In addition to Kenya, Surge has also been piloted in more than a dozen countries to date, including Burundi, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, Niger, Pakistan (the first Asian country to implement the program), Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan.

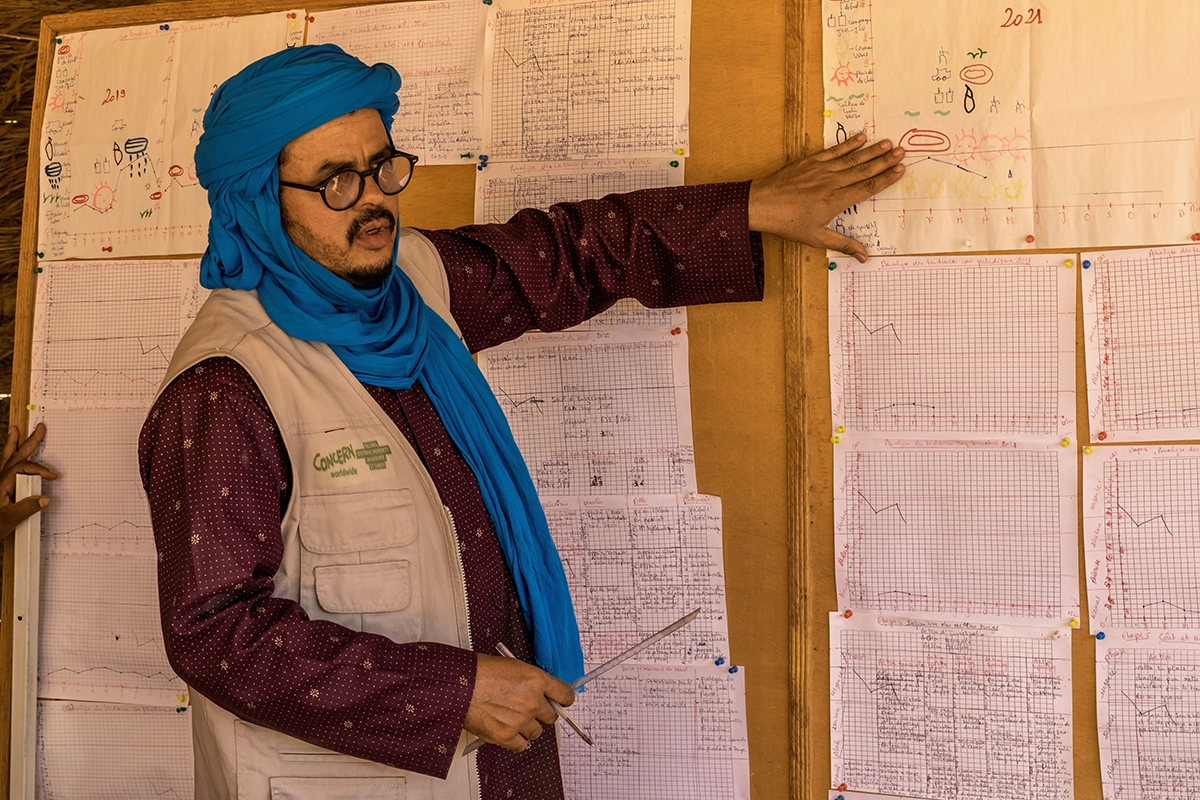

Some of our most recent success has come from Niger, as seen in families such as Mariama Badje’s. There, our Surge Approach has been implemented since 2016, and the program scaled up in 2021. “It allows us to always know where we are and what to expect. If we did not have it, we would feel less confident in our work,” said one head nurse at a facility participating in Surge in Tahoua.

More community

“We are starting to think about it for all the major illnesses. It’s like a quality-assurance approach,” adds another head nurse from a different clinic in Tahoua, who also notes that this quality applies to both the care that patients receive, and to the relationships among the staff of the clinic. “We work better as a team. Before, [the district staff] were like big chiefs — we were scared of them! But now we’re like friends as we’re together more often.”

Going beyond the national benchmark that local and national government authorities cover up to 50% of costs associated with the Surge Approach in the country, local districts in Tahoua cover 67% of the costs.

In fact, what began as a pilot program across eleven health facilities in the Tahoua region now covers over 470 centers across the country (nearly 150 supported by Concern). The Surge approach was integrated into Niger’s national CMAM protocol and, most recently, it helped to achieve the country’s 2020-2029 “Roadmap for the National Protocol for the Integrated Management of Malnutrition.”

Concern’s work to end hunger

From Afghanistan to Yemen, Concern’s Health and Nutrition programs are designed to address the specific, intersectional causes of hunger and malnutrition in each specific context. Our projects often combine two or more of the following areas of focus: agriculture and climate response, maternal and child health, education, livelihoods, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH).

We played a key role in developing Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), which has been recognized by the World Food Program as the gold standard for treating malnutrition. Other recent successes, like Lifesaving Education and Assistance to Farmers (LEAF) have seen entire communities not needing humanitarian food aid for the first time in decades due to holistic and systemic shifts in agricultural practices and community care.

Last year alone, Concern reached 5 million people with health and nutrition programs in 16 countries. Your support can help us to do even more in the year ahead.