Project Profile

Safe Learning Model

Developed by Concern, the Safe Learning Model takes a holistic approach to transforming education — and communities.

Read MoreWhile progress has been made in the fight for gender equality, gender-based violence (GBV) continues to be a major human rights issue around the world, affecting one out of every three women and girls. The UN’s 16 Days of Activism campaign begins annually on November 25 to raise awareness of GBV’s prevalence, challenge its causes, and focus on solutions. Here’s what you need to know.

The UN’s definition of GBV, which we’ll be sticking to, is any act of violence against women and girls based on their gender “that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering.” The UN adds that this can happen either in public or in private.

This can play out in countless ways, and there are many types of gender-based violence, some obvious, some less so. But some most common instances include domestic violence, sexual harassment, rape, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, so-called “honor” crimes, and online harassment.

In fact, one in every three women worldwide will be physically, sexually, or otherwise abused in her lifetime. That’s an estimated 736 million people.

Unsurprisingly, countries with higher levels of gender equality tend to have lower instances of GBV — though no country has managed to either foster full gender parity or completely eliminate gendered violence.

The opposite is also true. For example, the World Economic Forum ranked Pakistan as having the second lowest-level of gender equality in the world in 2024. Correspondingly, the World Bank has estimated that 29% of Pakistani women have experienced some form of intimate partner violence.

“GBV, in general, is a very sensitive topic to discuss in the context of Pakistan as it is considered as an internal issue of family and largely underreported. Women are expected to live with it as they did not think they had an option.” — Concern Program Participant, Pakistan

It’s likely that many governments don’t know the full scope of violence against women and girls within their countries. Despite its prevalence, it’s been a slow process to get a global body of evidence. Violence against women wasn’t officially recognized by the United Nations as a violation of human rights until 1992. Many women in countries with high rates of GBV don’t report their experiences because of a culture of silence.

Progress on this has been slow but steady. In 2010, for example, only 82 countries were collecting data on GBV cases. That number nearly doubled in just over a decade, with 161 countries reporting in 2021.

As mentioned above, it took a while, but for more than 20 years GBV has been recognized as a violation of human rights. It goes against the first article of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

GBV also threatens other fundamental human rights, including the rights to:

GBV is rooted in gender inequalities and culturally-specific patriarchal traditions, meaning that it’s a learned behavior. These forms of power and control — both explicit and implicit — continue to create social environments in which violence is both pervasive and normalized. However no one is born inherently violent, and we have to keep that in mind in designing effective solutions to gender-based violence.

Working with men and boys to “unlearn” harmful norms and behaviors, as well as with women and girls to understand their rights, are both foundational to ending GBV. Through Concern’s partnership with Sonke Gender Justice, we have led programs with this approach in over ten countries across Africa, supporting couples to transform their attitudes and behaviors together and move towards more positive and equitable relationships overall.

One of the biggest causes of gender-based violence is a crisis. During COVID-related lockdowns, calls to domestic violence helplines increased as much as fivefold in some countries. In many countries, the resources used to protect women and girls from GBV were also diverted for COVID-19 response.

Similar patterns occur in conflict-affected areas. Women and girls face many challenges during conflict, chief among them increased threats of violence, rape, and forced marriage.

Women who have experienced gendered violence are 50% more likely to be living with HIV. In sub-Saharan Africa, 80% of all new HIV infections in 10 to 19-year-olds are among girls.

Food insecurity also leads to increased gender-based violence. Women and girls face more early and forced marriages as families seek dowry payments and try to reduce their food bills. Women may turn to sex work to survive, and money shortages increase tensions within families, which can lead to violence.

Too often, girls experience GBV at school (or on their way to and from school). The issue is so prevalent it has its own acronym: SRGBV (school-related gender-based violence). According to the UN’s Girls’ Education Initiative, around one in three students experience physical violence, psychological violence, or bullying at school on a monthly basis. This threatens the same human rights for children as adults, as well as a child’s basic right to an education.

A 2018 study from UNFPA reveals that girls and young women with disabilities face up to ten times more gender-based violence than those without disabilities. Those with intellectual disabilities are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence.

Gender-based violence doesn’t exist on a binary. In the United States, transgender people are four times more likely to experience violence.

The risk for GBV also goes up in different areas based on race, ethnicity, immigration status, economic status, and a host of other compounding factors. The basic principle, however, is that the less equal a person is, the higher the risk for violence directed against them. While not all acts of violence are motivated (or solely motivated) by gender, it’s a common factor.

Abusers often use tactics that make it very difficult for women to escape domestic violence. In many cases, women who do try to leave an abusive partner in order to ensure their own safety as well as that of their children face an increased risk of ongoing and even escalating violence. Women are also prevented from leaving violent relationships because of shame and guilt, lack of safe housing, or the stigma of divorce — which, for women living below the poverty line, will leave them in an even more economically precarious situation.

Many countries still hold beliefs and laws built around the myth that forced sex within a marriage is acceptable. But rape is defined by an action, not just the identity of the perpetrator or survivor. In Malawi, the most prevalent form of sexual violence is marital rape. In response to this and other inequalities, Concern established a programme called Umodzi, which engaged couples to reflect upon issues such as gender norms, power relations, and healthy relationships in order to reduce intimate partner violence and foster gender equity.

People who experience violence react in any number of ways: anger, distress, grief, or no obvious reaction at all. We’ve been conditioned to expect targets of violence to be depicted as helpless, fragile, or distraught, though these are also harmful stereotypes. However, experiencing an act of violence doesn’t make a person broken. Survivors are not just capable of recovery, but also action and leadership.

No one should suffer or be marginalized on the basis of their gender. Concern’s approach to ending gender-based violence is part of our larger work to build gender equality — a critical factor in ending poverty and hunger.

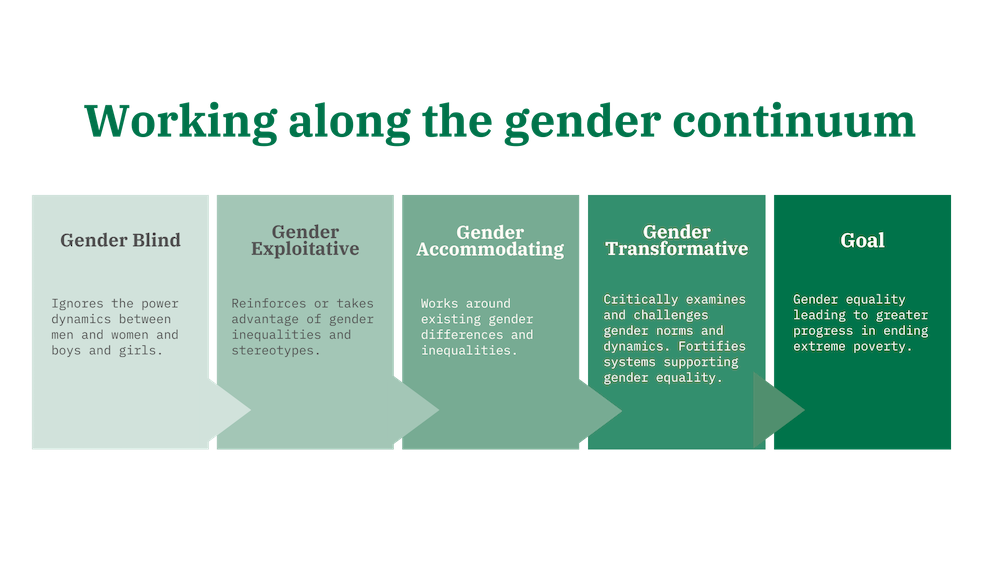

Regardless of our program focus, Concern integrates a gender-transformative framework in every country where we work.

We work with communities to identify, critically examine, and challenge the gender norms and dynamics that are hindering progress for everyone and design projects and responses that strengthen and support gender equality within a community.

Our emergency responses also prioritize women and girls, ensuring that they have access to the resources they need to stay healthy and safe during a crisis.