STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education is more than the sum of its parts. It’s a comprehensive and holistic approach that helps students think critically and develop innovative solutions to complex problems.

One of the most complex problems that STEM can help to solve is extreme poverty. Not only is STEM the fastest-growing job market, its frameworks are ideal for addressing the root causes of poverty in different countries and communities. The best sustainable solutions to poverty may not always be the most scientific or high-tech, but they are consistently driven by innovation and critical thinking. STEM education has led to innovations in key areas of sustainable development, particularly healthcare and agriculture.

This type of education produces “the competencies we need to transform our country into a newly industrializing middle-income country,” as Dr. Amina Mohamed, Kenya’s former Cabinet Secretary for Education, said in 2019.

Nurturing every learner’s potential

With 37% of its population aged 14 or younger, Kenya is one of the countries that has committed to STEM as part of broader educational reforms. In 2018, the country launched a new strategic plan for national education, committing more than 5% of its GDP to the sector. A large part of this plan centered on two initiatives. The first was a standardized Competency-Based Curriculum, which shifted focus from teaching students what to think to teaching them how to think.

This ties in with the STEM principle of critical thinking, and it was one way that education officials were hoping to prepare more children for further studies in this area. The country’s Ministry of Education also established three tracks for secondary students to pursue: Arts and Sports Science, Social Sciences, and STEM. The core idea behind these reforms was captured in a phrase used often by officials: “nurturing every learner’s potential.”

This was, as several researchers from the Harvard Graduate School of Education noted, a major break with tradition, challenging many “deeply-held cultural perspectives on education’s purpose and content.”

However, some of those perspectives were ready to be challenged: Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 93% of Kenyan children nationwide were enrolled in primary school, but only 53% continued on to secondary school. Even primary school enrollment was a challenge in some areas of the country.

A complex issue

One of those areas is Marsabit County, the second-largest county in Kenya (accounting for roughly 11% of its total area). Much of that land, however, covers Kenya’s arid and semi-arid land in the north, and many residents rely on agriculture and pastoralism for their livelihoods. With drought an increasing threat in the area (including the recent Horn of Africa crisis), roughly two-thirds of people in Marsabit live below the poverty line.

It’s largely because of this that primary school enrollment in the county has been historically low at less than 50% — nearly half the enrollment rate of the national average. Years of consecutive failed rains led many parents to take their children out of school because they couldn’t afford the fees. Many were also forced into child labor to help with the family income. One of the prevailing attitudes in the county was that education wasn’t important or valuable enough to justify the other challenges and conditions that farmers and pastoralists were facing.

This is also one of the key arguments for STEM: While industries like agriculture struggle against increasing environmental issues and risks, STEM can help the sector recover through methods like Climate Smart Agriculture and disaster risk reduction. It can also provide alternative career paths for students that will earn more money while working to build Kenya’s economy. But we can’t get to that point without STEM skills being part of education from the get-go. And we can’t build those skills into the curriculum without the right resources.

An innovative solution

Of the 192 middle schools in Marsabit County, 90% lack the capacity to offer STEM subjects as part of the new Competency-Based Curriculum. They don’t have the laboratories or equipment for the practical sessions (a huge component of STEM’s hands-on approach to learning). Many also lack teacher capacity and materials for most subjects, including STEM.

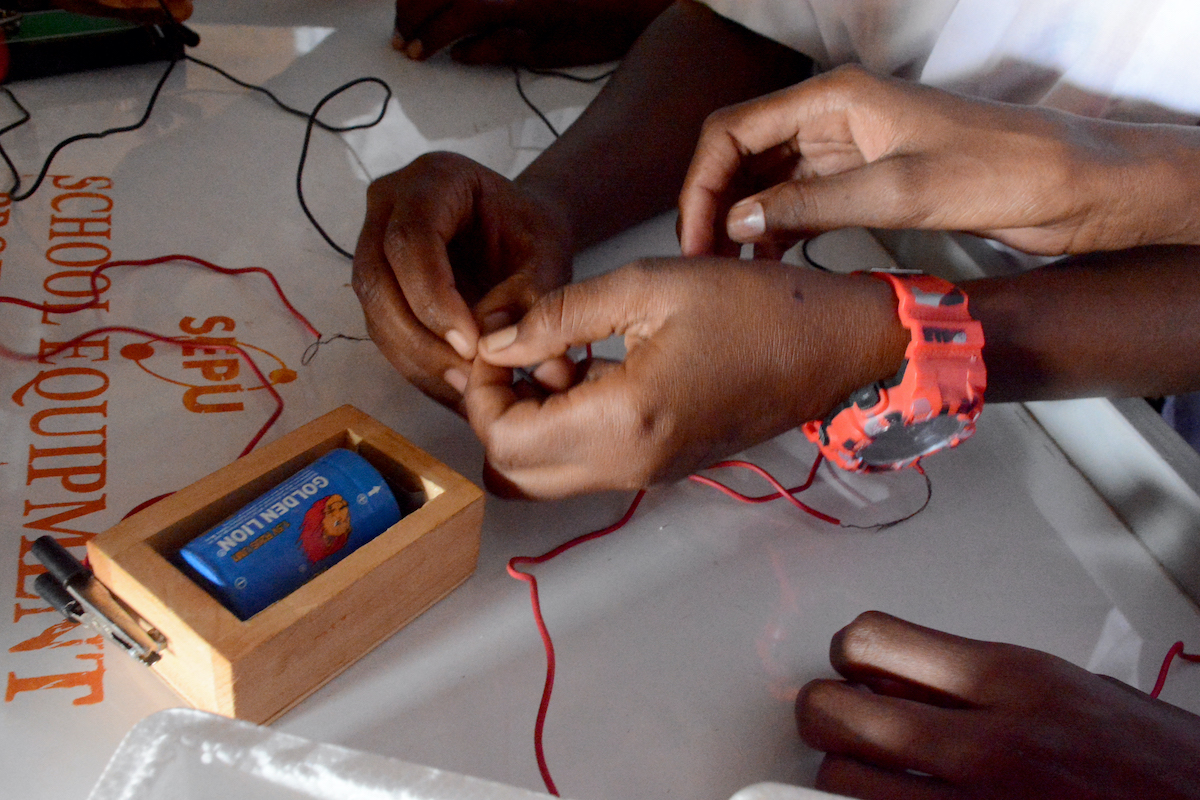

Concern has worked to address these challenges through two education projects in Marsabit. With funding from the Datatec Group, we worked with the government’s School Equipment Production Unit to deliver science kits to nine of these schools, and also installed a mobile laboratory that provides the learning environment.

“Having the mobile lab in our school is a very important thing,” says Brian Anungo, a teacher at the Kalacha Nomadic Junior Secondary School whose classes focus on integrated science, agriculture, and nutrition — a highly valuable combination in Marsabit.

As Anungo explains, theory is important for his classes, but it can be difficult for the kids to engage and fully understand the material. In the practical sessions, however, “we do the real thing,” he says. Students get to see how the theory is applied to real life, “and then the lessons always seem interesting — our students participate actively.”

Shaping the future — and the present — with STEM

Education is a long-term investment, but some of the students in Concern-supported schools are already reaping the benefits of access to STEM.

“We never thought that we could win a trophy because of science,” says Boru Ali, a head teacher at the Bubisa Primary School in Marsabit. “We are saying now that we can do more.”

The trophy came from a science fair, in which students from Bubisa participated (and won) after broadening their STEM horizons in a Concern-supported mobile lab.

“When Concern brought the science equipment, the students were excited, the teachers were happy,” Ali says. That enthusiasm kept the seventh and eighth graders in the mobile lab for practical lessons. Teachers and school administrators saw the improvements early on, with children moving from an average grade of 54 for science to an average of 67.

Those results were symbolized by the trophy students from Bubisa Primary School won in 2023 at the county-wide science fair. As part of that win, they also traveled to Nairobi for Young Scientists Kenya’s National Science and Technology Exhibition, further broadening their horizons. However, true to STEM’s core idea of teaching students how versus what to think, Ali notes that the greatest change in this curriculum has gone beyond any scientific principle or subject.

“What changed most is their attitude,” he says. “Initially students, especially girls, weren’t encouraged to take science subjects. They always had low motivation towards mathematics and science. But when you look at them now, they’re really motivated.”

A lifetime of learning

Ali adds that parents have also become motivated. Watching their children succeed has helped them see the value in STEM and how the next generation of Kenyans may apply those learnings within their own communities. With Datatec’s support, Concern was able to increase the number of schools in Marsabit who have sufficient STEM resources by more than 50%, in turn enabling nearly 1,200 students to develop skills aligned with the Competence-Based Curriculum.

In its own way, this project also demonstrated what’s possible with a STEM approach — breaking down a complex issue into manageable components, and laying the foundation for continued innovation and a lifetime of learning.

Concern’s work in education

Concern’s work is grounded in the belief that all children have a right to a quality education. We integrate our education programs into both our development and emergency work to give children living in extreme poverty more opportunities in life and supporting their overall well-being. Our focus is on improving access to education, improving the quality of teaching and learning, and fostering safe learning environments.

We've brought quality education to villages that are off the grid, engaged local community leaders to find solutions to keep girls in school, and provided mentorship and training for teachers. Last year alone, we reached over 690,000 people with education programs across nine countries.