News

Explainer: What (and When) Is A Famine?

More on what a famine is, when it’s declared, how it’s measured, and the long-term impacts famine can have on individuals, communities, and countries.

Read MoreOn some level, we all understand what hunger is. Chances are, it’s a feeling you’ve experienced recently.

But one little word contains a lot of different meanings, especially when we consider the difference between how we feel when we’re late to have lunch and the global issue we’re addressing in the countries where hunger rates are not only high but also deadly. Read on to learn more.

The Food and Agriculture Organization lays out a practical definition of hunger:

“Hunger is an uncomfortable or painful physical sensation caused by insufficient consumption of dietary energy. It becomes chronic when the person does not consume a sufficient amount of calories (dietary energy) on a regular basis to lead a normal, active and healthy life.”

This may not be new information, but it’s helpful to have in mind when we talk about hunger as a larger issue. Important in this FAO definition is that it recognizes that hunger is a spectrum: We all get hungry, but for some people that experience is the rule versus the exception. That’s when it becomes a problem.

Hunger is a broad concept, focused more on the physical and psychological experience of going without food than on the more quantifiable nutritional aspects and physical outcomes we associate with good nutrition. That’s where a few other terms come in handy:

Food security: The measure of an individual’s ability to access food that is nutritious and sufficient in quantity. (Learn more in our explainer on food security.)

Undernutrition: When a person doesn’t get enough energy and nutrients to maintain their normal activity and support the growth and development of their body. This can either be broadly (not getting enough food) or more specific (such as micronutrient deficiencies).

Malnutrition: Malnutrition is a broad way of talking about undernutrition or overnutrition. The latter happens when a person takes in more nutrients or energy than is necessary. While this can lead to other health issues, when we talk about malnutrition in the context of our work, we are usually talking about undernutrition.

Acute malnutrition: Below-average weight in proportion to height (also known as wasting) due to nutritional deficiencies, either from poor intake or poor absorption of nutrients. Children who are acutely malnourished are usually diagnosed with one of the following two types:

Chronic malnutrition: Also known as stunting, this is when malnutrition is an ongoing condition that leads to a person having a lower height for age — at least two standard deviations below the median.

Those are a lot of words, but they all work together to create and maintain the current global hunger crisis. If a person, family, or community doesn’t have the access they need to sufficient and nutrient-rich food, a momentary hunger can escalate into one or more forms of malnutrition.

For many, especially young children, immunocompromised people, and elders, this can be a death sentence. It’s not the hunger itself that’s the real killer; it’s usually conditions that are easier to develop and harder to cure as a result of malnutrition. Not enough energy and nutrients means that people’s immune systems are more susceptible to communicable diseases.

Areas with high hunger crises also tend to have other public health issues, such as tainted water or a lack of adequate sanitation infrastructure. If an outbreak of cholera or diarrhea hits, the effect can be catastrophic.

“Famine” is a word that is often used (and misused) for emotional or metaphoric effect to describe food crises of varying size and scope.

There are, however, clear criteria for what constitutes a famine. A famine is declared when:

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) is the organization tasked with monitoring countries and regions facing famine or famine-like conditions. We rely on their data to know when this is happening.

There are a few different ways of measuring hunger that lead to different ways of talking about how many “hungry” people are in the world. It’s a multidimensional issue, so no one number is going to give us all of the information we need to know.

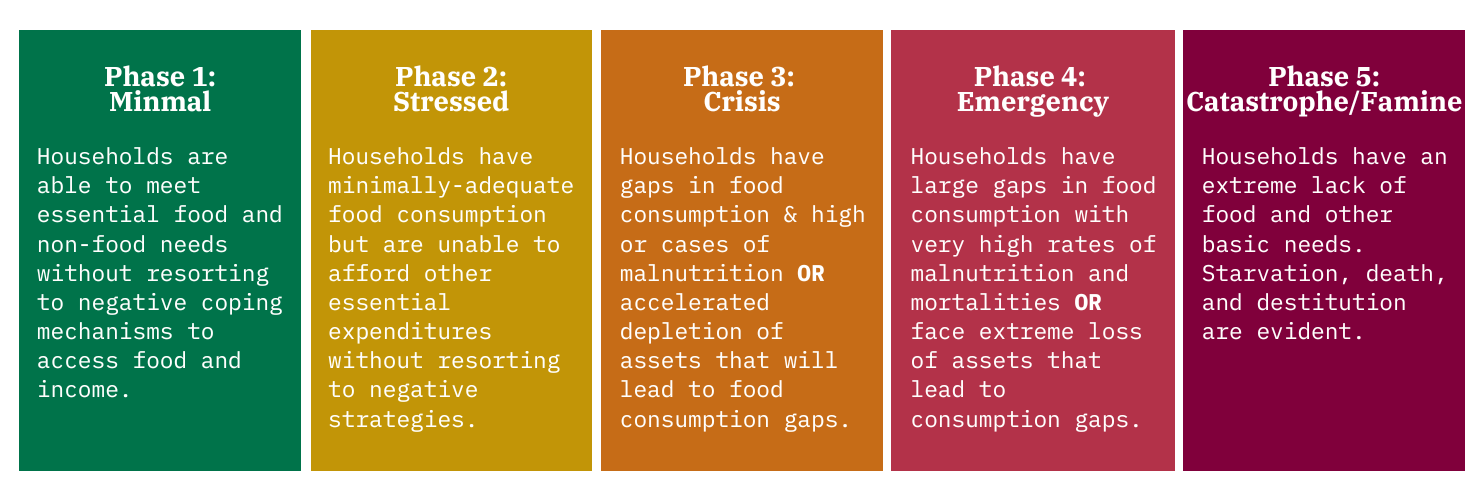

The IPC focuses on food security, and rates countries and regions on a scale of 1 to 5:

Phase 1. Generally food secure communities usually have a reliable source of food with low-to-moderate risks for crisis-level food insecurity (Phases 3, 4, and 5)

Phase 2. Moderately food insecure communities have a borderline reliable source of food, and have a recurring high risk for food insecurity (due to a combination of vulnerability to risk and possible hazards like a natural disaster or conflict).

Phase 3. Acute food and livelihood crisis (sometimes shortened as crisis-level) food insecurity happens when a community is highly stressed due to any number of causes, resulting in a critical lack of food access that results in higher-than-normal levels of malnutrition and loss of livelihoods. If these circumstances continue, the crisis will become an emergency or famine.

Phase 4. Humanitarian emergency (or emergency-level food insecurity) is declared when there is a severe lack of food access with higher than average levels of mortality, malnutrition, and loss of livelihoods that the FAO would term “irreversible.”

Phase 5. Famine/Humanitarian catastrophe (also known as catastrophic-level food insecurity) is when the criteria for a famine are met. This is a situation that the FAO links to forced migration and social upheaval.

Other organizations look at other indicators. In compiling the peer-reviewed Global Hunger Index each year, Concern and partner Welthungerhilfe look at four key indicators:

All of these terms are admittedly very clinical ways of looking at a problem that has severe ramifications for people living in dire circumstances. However, this is just one way of looking at the problem, and a necessary one if we’re going to make progress in ending hunger.

While overall levels of hunger around the world had been going down since 1980, we’ve started to reverse course following the COVID-19 pandemic, an intensification of the climate crisis, and increased conflict. Today, one out of ten people still moves between Phases 3, 4, and 5 of food insecurity, and it’s important to know who is moving where so we can focus on the most urgent cases accordingly.

Much like the cycle of poverty, hunger is also a cyclical issue, where people move in and out of different phases throughout a year or a lifetime. Hunger doesn’t define a person as much as it does their current circumstances. However, the more it continues, the more likely it will permanently affect that person’s future.

As we mentioned earlier, hunger doesn’t work alone. From cholera to conflict, it’s an intersectional issue and one that we have to treat as such in order to sustainably end it.

Concern’s current nutrition strategy focuses on many of these intersectionalities, designing programs that respond to both sides of the coin. In addition to providing frontline food assistance and longer-term solutions in conflict settings, we also focus on these four key areas of nutrition:

Agriculture: Agriculture plays a key role in ending hunger, especially in majority-agrarian countries. We work to not only increase the quantity of harvests but also the quality so that crops can survive and thrive in the face of the climate crisis and deliver key micronutrients that people need on a daily basis.

Livelihoods and cash: Agriculture and livelihoods go hand-in-hand in many countries. We work with families to improve their harvests and the business side of their farms, linking food security with financial security. Where possible, we also help families identify other sources of income that they can use as insurance against climate emergencies. When an emergency hits, cash transfers also help ensure that people are still able to eat and recover lost assets.

Maternal and child health: The first 1,000 days between conception and a child’s second birthday are a key period that can determine their health for the rest of their lives. We work with pregnant and breastfeeding women to ensure that they are set up with all of the nutrients they need (especially during pregnancy). Our nutrition programs also include the standard-setting Community Management of Acute Malnutrition, which helps to monitor undernutrition as children grow.

Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH): Ensuring that communities have access to clean water and hygiene/sanitation services not only means that they can keep their crops and livestock well-maintained, but also that they will be less susceptible to waterborne illnesses that may prevent them from absorbing nutrients.

From Afghanistan to Yemen, Concern’s Health and Nutrition programs are designed to address the specific, intersectional causes of hunger and malnutrition in each specific context. Our projects often combine two or more of the following areas of focus: agriculture and climate response, maternal and child health, education, livelihoods, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH).

We played a key role in developing Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), which has been recognized by the World Food Program as the gold standard for treating malnutrition. Other recent successes, like Lifesaving Education and Assistance to Farmers (LEAF) have seen entire communities not needing humanitarian food aid for the first time in decades due to holistic and systemic shifts in agricultural practices and community care.

Last year alone, Concern reached 9 million people with health and nutrition programs in 21 countries. Your support can help us to do even more in the year ahead.