It’s a technical phrase for an everyday event — and ultimately it’s about making sure people have enough to eat. Here’s what we mean by a food system.

It’s a word that’s becoming increasingly popular, especially in humanitarian and development circles. Last year, the World Food Programme won the Nobel Peace Prize for an approach that, in part, rests on the idea that hunger is a weapon of war, and a strong and secure food system is necessary for peace.

But what exactly is a food system?

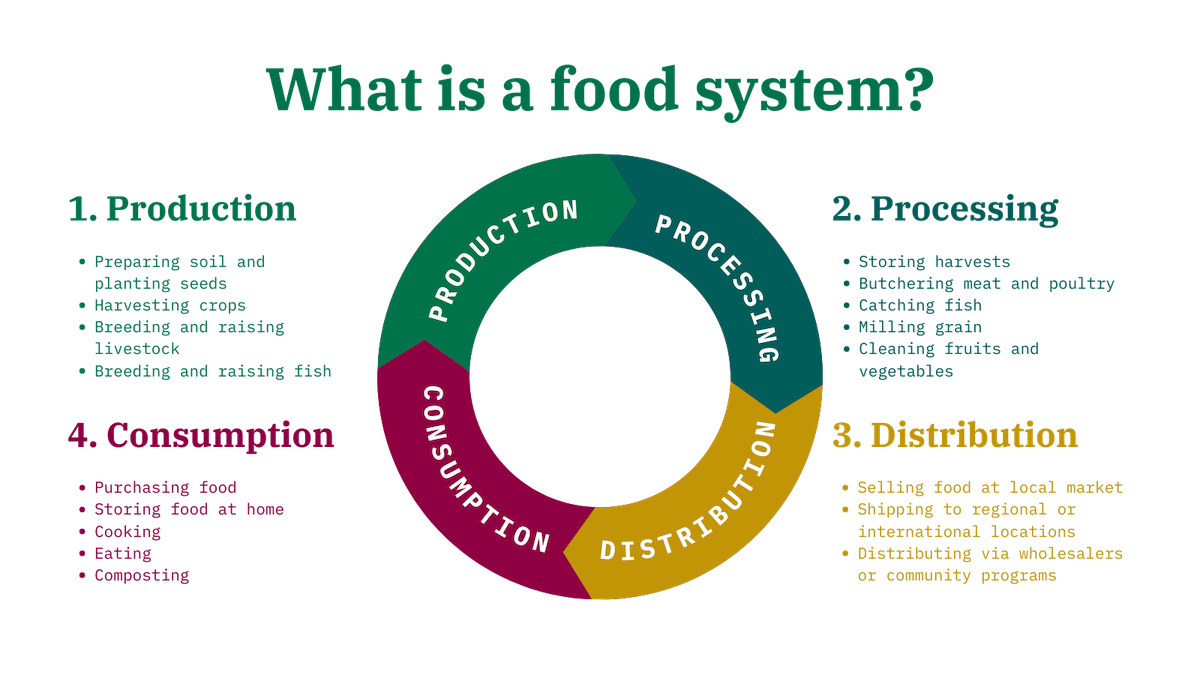

A food system is, at its core, the cycle in which food is produced and prepared for people to then buy, cook, and eat. Food systems can be complex or simple — covering a small farming community in the remote highlands of Ethiopia, or encompassing the vast system that connects farms to tables in the United States.

The most important thing about food systems for our work at Concern is that all parts of it need to be working in order to ensure that communities reach low levels of hunger and malnutrition, and have a form of stability in their health and nutrition on which they can build a stronger community overall. Hunger is one of the biggest deterrents to ending poverty (and many of poverty’s other causes, like conflict). By ensuring that people not only have enough food today, but the means of getting enough food every day, we’re able to get one step closer to Zero Hunger — and Zero Poverty.

The parts of a food system

Here’s how that works in four simple steps.

1. Production

The first step of a food system is also the most variable, depending on what you’re… well… producing. Anything that can be produced “raw” is covered under this stage, including fruits, vegetables, grains, meat, eggs, and milk.

In agriculture, production consists of the techniques for farming the land (including Climate Smart Agriculture and other responses to climate and soil changes), tilling the soil, planting and cultivating crops, and harvesting. Production also includes breeding and raising fish, livestock and poultry, for both their meat and for their byproducts.

Climate response and resilience is one of the most important ingredients in the production phase of a food system, as much of what we eat begins as a crop or an animal that relies on pastureland. (And, of course, both crops and animals rely on access to water.) However, many of the causes of hunger are felt at the production stage: Conflict destroys farmlands, leaving them scorched and unusable, sometimes for years. A pandemic may lead to lockdowns that prevent farmers from going to their land if it’s not in their backyard — forced migration leads to similar outcomes. Infestations, like the 2020 locust crisis, could destroy crops before they’re ready for harvest. An economic downturn may leave farmers able to afford less in terms of seeds and fertilizer, or forced to buy poorer quality inputs that yield poorer harvests.

2. Processing

Once crops, meat, eggs, and milk have been harvested, those inputs can be processed. This may be as simple as washing the extra dirt off of root vegetables or filtering out any apples that have gone bad. This could also involve butchering meat for a local or international market, turning milk into butter or yogurt, or milling grains into flour or cereal.

Food storage is also key in processing, especially in low-income rural areas where farmers may have good harvests but lose a good portion of their wares due to poor storage facilities. This is true for both meats (which require refrigeration) and grains (which need functioning grain stores). Addressing this challenge can require large interventions, like rehabilitating facilities that serve entire communities. Some changes can happen at the household level: One innovation Concern has introduced into women’s groups around the world are solar dryers, which serve as one solution. Sun-drying vegetables, a traditional practice, preserves micronutrients and prolongs shelf lives.

3. Distribution

This is when food begins to reach the consumer. Many of the farmers and other food producers Concern works with sell their wares at local markets, which is where they also buy their own family groceries. In some cases, the distribution can go a bit further — the businesswomen who form the Chalbi Salt Self-Help Group travel two days on foot to gather natural salt deposits from northern Kenya’s Chalbi Desert, making a 24-mile round trip to sell locally within their community and those just across the border in Ethiopia. In the US, we’re used to food traveling even further across the country (and, at times, across borders).

The distribution phase of the food system is also where food is sold to wholesalers, community programs, and local merchants. Marketing and business skills come in handy here, which is why we factor them into our Graduation programs and other livelihood initiatives. A small network of income-generating projects run by Concern in northern Lebanon for both Syrian refugees and members of the host community not only taught women the basics of dairy production, but also the ways in which they pitch their fresh cheese and dairy to local shops with confidence and ease.

4. Consumption

When food reaches the consumer, this is — as the word would suggest — the consumption phase of a food system. However, this goes beyond eating: Consumption is everything from purchasing the food, to storing it, to cooking, and eating it. In some more complex models of the food system, composting old food would be its own phase, but we can also include composting and other forms of disposal (whether it’s wasting food that didn’t get eaten in time, or disposing inedible parts that can’t be composted).

What’s available to communities and what people can afford are two big factors that shape the consumption cycle. Inflation due to the crisis in Haiti, for example, has made basic staples of nutrition almost impossible to afford, with one recent World Food Programme report estimating that a working Haitian spent 35% of their daily income on one meal — which is akin to someone in New York paying $74 for lunch.

Changes in consumption can also influence changes in production. With staple crops like sorghum suffering in an increasingly drought-ridden district in northern Ethiopia, the hardy mung bean was, on paper, a sound, drought-resistant alternative. Farmers in the region were initially skeptical of switching crops — a risky endeavor. However, cooking demonstrations helped to show that the crop was delicious and versatile. It’s now so popular in the region that it sells for four times the price of sorghum.

How Concern works with food systems

For most of our five decades as an organization (and counting), Concern has led the way with standard-setting programs that strengthen local food systems and provide quality nutrition support to the world’s most vulnerable communities.

Zero poverty is only achievable if we also reach zero hunger. We work towards this by addressing malnutrition, along with the overall health and wellbeing, in the communities we serve. Specifically we focus on those most vulnerable to malnutrition, including children and women who are pregnant, breastfeeding, or of age for pregnancy. We balance rapid response with long-term solutions that address many of the root causes of hunger.