What We Do

Our Work: Education

Concern Worldwide has extensive education programs in over a dozen countries, reaching millions of young people with vital services. Learn More

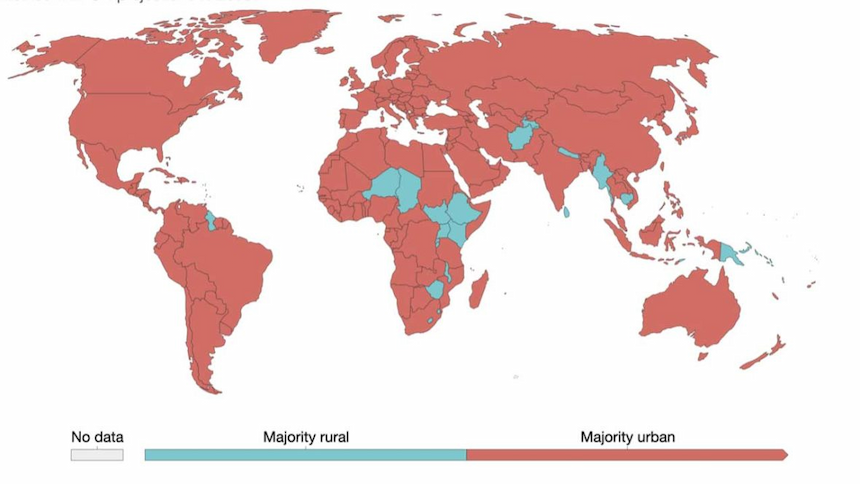

Read MoreIt’s predicted that 68% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by 2050. That’s nearly 7 billion people, according to the folks at the UN with the big calculator. And as many as two-thirds of them — about 4.6 billion — will live in slums.

Content Advisory: In this article we use the word “slum”, the most commonly used description for informal urban settlements. Concern fully supports the drive to update terminology used in the development sector, especially when it has derogatory connotations. On this occasion, because so many of the people who live in informal urban settlements themselves use the word slum, we have made the decision to use both.

4.6 BILLION human beings living in urban informal settlements by the year 2050. Hardly a vision of an ideal world, by any stretch of the imagination. So why is this a thing? Why are more and more people packing themselves into crowded spaces, with all of the accompanying discomforts and daily life challenges? Especially when there’s a whole world of fertile valleys, rolling hills, and open plains that could easily accommodate (and feed) all of us.

There’s both a compelling logic to this mass urbanization and a strong case for trying to reverse it. Read on for our take on the what, who, why, and how of slums.

First off, what is a slum? According to the World Health Organization, a slum household is defined as a group of individuals living under the same roof lacking one or more of the following conditions:

Doesn’t sound very appealing right? Well, it’s all relative.

“At least here in the city my husband can find work and there are more opportunities”

Take the example of Rena, a mother of two we met on the streets of Dhaka in Bangladesh some years back. Her home was literally a square of pavement — actually a step down from a slum — where the family cook, eat, and sleep. They survived on money raised from petty trading and the casual labor jobs her husband picked up.

But life where they came from, a rural area in the vast river delta that forms the southern part of the country, was even more difficult. The only reason they even had access to land was that they lived on a char, an alluvial island that regularly disappears under flood waters, taking with it everything they owned and sometimes even putting their lives in danger. Rena told us “At least here in the city my husband can find work and there are more opportunities,” she said.

Dhaka has more than its fair share of slums. Sprawling, ramshakle settlements made from timber and tin and rags, with jerry-rigged water and electricity for those who can pay, and a complex system of ownership and governance. According to the World Bank, nearly 50% of urban dwellers in Bangladesh live in slums. The UN says that nearly 60% of that country’s total population will be urban by the year 2050. In Dhaka alone there will be 30 million people by 2025.

Of course, people living in informal urban settlements are not a homogeneous group. For example, there are people with regular jobs, tenancies, formal ID documents, and even semi-formal arrangements for utilities like electricity and water. Then there’s the “floating population” which tend to be more transient, less engaged with any systems, and generally less economically secure.

Then there are different ethnicities and minority groups — in the case of Bangladesh this can include the Dalit, Hijra (trans gender), Bihari (Urdu speaking), Bede (semi-nomadic boat community), among others. Often it is these groups who are most excluded and at highest risk of falling into long-term extreme poverty

As for who owns the land, how it’s allocated, and who administers the provision of services, that’s a complex question with multiple answers. For example, in Kenya, much of the land that constitutes Nairobi’s sprawling slum communities is government-owned, but has traditionally been managed by a variety of private interests, with benefit often accruing to those with strong political connections. Efforts have been made to establish land management committees, made up of community representatives, but progress can been slow.

Support Concern's work to eliminate extreme poverty

In many slums there is electricity and water available, but it’s often stolen by “entrepreneurs” who tap into public power lines and resell to individual households for profit. It’s a lucrative business model, generally controlled by those who have the means to enforce that control. For example, in the slums of Port-a-Prince, Haiti, power and water is mostly controlled by gangs, who use threats and violence to protect their business.

Sometimes, a more traditional business model, involving diesel-powered generators, is in place for those who can afford the fees. You'll also see solar panels dotted throughout settlements, mostly for phone charging and lighting. Local and national governments have in recent years begun to formalize some of the utilities available within slums, to varying effect.

Education is, in the words of Concern legend Aengus Finucane, “the key to everything.” It’s a precious commodity and one for which parents in most informal settlements must pay. Such was the case in Nairobi’s Mathare slum for many years, where all elementary schools were privately run, often set up by parents, and provided a wildly varying quality of education.

Many teachers were themselves poorly educated, and attendance by pupils was dependent on their parent’s ability to pay and the child’s availability to attend. A lot of children are involved in the daily grind of generating income for their family. For many years, Concern ran programs supporting informal schools in Mathare, but over the past decade the Kenyan government has begun to regularize elementary education within this and other settlements.

Attaining a second-level education can be little more than a dream for many kids who live in the slums, especially girls. Families often rely on the generosity of sponsors to fund their attendance at boarding schools. Marystella Barasa, who has lived in Ngando settlement all her life, is one of 3,000 young Kenyans who have been supported to attend high school through a Concern program called “Let All Girls Succeed.”

She is determined to get maximum benefit from her good fortune and also to pay it forward to others. “Now I have seven girls whom I mentor. Some have experienced many struggles in life,” she says. Marystella intends to dedicate her career to helping others, with plans to train as a teacher. “I don’t just want to do teaching to earn a wage,” she explains. “ I want to help my young sisters out there to rebuild their self-esteem.”

Probably one of the most famous of all the urban slums is Kibera, a sprawling neighborhood in Nairobi, famed for its proximity to a huge landfill site. When we met Margret, she was living in a single room in the Makina neighborhood with her two children and a friend. There was no electricity, only one bed, and the roof leaked during the rainy season. Margret’s family migrated from a village in the countryside when she herself was just child, her parents deciding that the city provided more economic prospects than where they lived at the time.

"I love where I live"

Life has been a series of ups and downs for Margret, but she has managed to survive, doing laundry for income and relying on the goodwill of others when times were tough. At one point, during the COVID pandemic, her youngest child became seriously malnourished and ended up in treatment.

But for Margret this is the only home she has ever really known. “I love where I live,” she told us. “It’s quieter than other parts and I can leave my baby with my friends here… but I would like a house that the rain doesn’t get into, somewhere that’s dry.”

Support Concern's work to eliminate extreme poverty

Good sanitation and hygiene are a massive challenge for almost everyone who lives in a slum, which of course has consequences for people’s health. Because of the informal nature of these settlements, access to clean water and functioning toilets is at best intermittent. Also, because most slums have developed on marginal and unused land, they are often prone to flooding.

This combination of factors, coupled with high population densities, means that water-borne diseases are much more prevalent than in other communities. Outbreaks of cholera can be deadly and difficult to control, especially when health facilities are few in number and poorly resourced. High density can also be an issue when it comes to contagion, as evidenced during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone in 2015.

Cité Soleil is a slum in the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. It has developed a notorious reputation for poverty and violence, fueled by gang wars and the effects of a spiraling economy. It’s home to over a quarter of a million people, squeezed into about eight square miles of marginal land between they city’s airport and the shores of the Caribbean. That’s some serious density, considering the majority of buildings are single-storey.

“This is a place where people are not living in a good situation,” according to 18-year-old Fefe. “When you wake up in the morning the first thing to greet you is rubbish. Here you will see armed men, dead bodies, no sanitation. The way people live is inhuman.”

Yet people stay, partly through lack of choice, but also because of the sense of community and kinship that has underpinned their lives here. They hold onto hope, waiting for better days. Community activists like Ernanciy Bien-Aimée advocate for outside investment and support at every opportunity. “We are not without hope, even at the worst of times,” she says.

Meanwhile the demographic majority in Cité Soleil is impatient for change. “Young people need recreational spaces,” Fefe tells us, “where they are not sitting down waiting for someone to give them a gun instead of a notebook.” His friend echoes that sentiment. “We need peace and normal services. Then life will smile on us again.”

One thing that’s common to every informal urban settlement you’ll visit anywhere in the world is an intense level of activity and enterprise. Life in the slums is about hustling for a living. Slum dwellers have office jobs, run trading enterprises, cook, bake, build, recycle, fix, fish, teach, learn, grow, buy, sell, deliver, entertain, and engage in a million different activities every day.

Artist Faith Atieno was born and raised in Kibera, and she loves it. “It is home and it is an exciting and vibrant place to live,” she says. She took part in an arts program in high school and quickly realized that the creative world was where her future lay. Although there were no post-school art classes in Kibera, Faith spent time with local artists and developed her craft and style through osmosis and experimentation. Street art has been a key part of her output.

Today, Faith runs a collective called Art360, a community-based organization with the goal of using art for change. “We aim to inspire and educate, and also provide a space for kids to be creative… and to earn something from it.” In late 2022, the collective secured backing to establish a web-based sales platform and international delivery service, bringing them one step closer to making that aim a reality.

It’s obvious that many people have figured out a way to make slum life work for them and have even managed to thrive in some of the most densely populated, economically disadvantaged environments on the planet. But, given the choice, it’s fair to say that most would prefer life to be less stressful and precarious, especially for their children.

Making this a reality will most likely take an integrated approach by governments and local and international NGOs. Improving living conditions within informal urban settlements is an obvious element of any solution. In the words of one Bangladeshi government official: “In the past, there was a push to send back the poor living in the slums to their villages. But we have shifted our position. We understand that these people are here to stay and are not going back. That is why we have the slum development section, and whenever we introduce programs or strategic plans, we try to incorporate them.”

Supporting business development for women — who often have fewer job opportunities outside of their community — is one way to help families build sustainable income and savings. Rina Akter, who lives in a settlement in Dhaka, worked with the Concern livelihoods team to launch her small business. " With the support of BDT 10,000 (US$100) and some training, I started business locally, selling vegetables in the local market. I now have daily income and enough to meet my family expenses and my business is encouraging other women in the community.”

Another approach to the issue is to look at ways of stemming the flight of population from rural areas, where poverty, climate shock, and land ownership restrictions drive people towards the big urban centers. Remember those startling urbanization statistics we discussed at the start?

Concern Country Director in Haiti, Kwanli Kladstrup, says longer term solutions could include increased support for indigenous food production and processing, making rural life more attractive to young people. “There’s great potential for more resilient market-based livelihoods, especially around climate smart agriculture practices, and for more inclusive urban-rural trade linkages to give increased returns on assets and effort“.

As with any issue that involves human beings, the answer to our question “Why do people live in slums?” is nuanced. “Because they have no choice” is an obvious one, but so too is “Because it’s home, it’s what they know, and it’s where their people are.”

Concern Worldwide works with urban slum communities from Asia to Africa to the Caribbean, supporting programs in education, social protection, water and sanitation, vocational training, nutrition and health, livelihoods, and much more. And in the countryside — from which so many people migrate — those programs are mirrored, in support of rural communities struggling to survive, thrive, and provide a livable environment for future generations.