Back to school has a whole new meaning when it’s not taking place in your mother tongue. We're working to break down language barriers in the classroom. One solution? Give children more time to transition from their mother tongue to their national language.

Picture it: You show up for your first day at school, and the teacher starts talking to you in a language you don’t understand. You’re now expected to learn to read and write in this language. Imagine if there were two new languages for you to learn. One more thing: You're only 4 years old.

For most kids in Kenya, that’s exactly the scenario they face when starting school. Language barriers in the classroom are ubiquitous in a country that has 2 official languages and 66 local languages. In Marsabit, the first language for most children is Borana. Once they start school, they must learn two new languages to understand their teachers: Swahili and English..

From an educational perspective, the results are disastrous. UNESCO estimates that 40% of school-aged children don’t have access to education in a language that they understand.

If all students had basic literacy skills, UNESCO estimates that 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. Language barriers mean that, despite years of schooling, many students end up essentially illiterate.

Language Barriers In The Classroom Leave Kids Behind From The Start

Despite years of schooling, many language minority students end up essentially illiterate.

“What we learned [from carrying out assessments] is that, by the time they’re in grades six, seven, and eight, children still can’t read and can’t write,” said Concern Kenya Country Director Wendy Erasmus. “They can recite what’s in a book — but they don’t understand it.”

Of course, it’s not just a Kenyan problem. Thousands of miles across the Atlantic in Haiti, classes are taught in French and Haitian Creole. However, either or both of these are foreign languages for many Haitian children. A World Bank-supported study showed that 76% of first graders, 49% of second graders, and 29% of third graders could not read a single word of Haitian Creole. Similar results were found when the same students were tested in French.

How Language Barriers Keep Language Minority Families In Poverty

For any student, basic literacy and numeracy skills are key to building a quality education. Even with just basic reading skills in place, UNESCO estimates that 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. Imagine the waste of going through an entire childhood worth of schooling, and still be unable to read.

Students learning a second language often struggle to express themselves if they don’t have a full command of that language, notes John Schumann of UCLA’s Department of Applied Linguistics. This can lead to emotional stress and affect their ability to learn.

Parents may also not speak the language used in school. This hinders progress even further when they can't understand their children’s homework in order to help them complete it.

As UNESCO notes, language is a double-edged sword. “While it strengthens an ethnic group’s social ties and sense of belonging, it can also become a basis for their marginalization.”

Rewriting The Rules — In The Mother Tongue

One solution to these language barriers is the concept of teachers leading earlier grades in the students’ first language. Tests in both Kenya and Haiti, as well as Liberia and Niger, showed promising results.

“Children can get comfortable with reading and writing in a language that they know,” explains Wendy Erasmus in Kenya. “Then over year three and four they phase into English and Swahili.What we’ve seen is terribly exciting… an impressive increase in these children’s ability to read and write.”

This method is in line with UNESCO’s recommendation for early teaching in the mother tongue. Gains from this early education will be sustained as students transition into classes taught in a national language. Bilingual training for teachers is also a critical element for success.

Concern has been supporting these initiatives with curriculum design, training classroom teachers, and providing learning materials.

“A Continuation Of What They Have Learned At Home.”

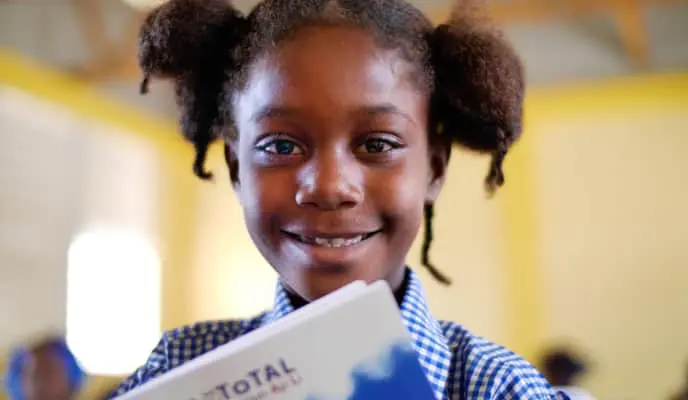

Meanwhile, in the second grade classroom of St. Peter’s Primary School in Sagante, Kenya, teacher Mr. Sode asks a question in Borana. In response, 6–year-old Daki Guyo enthusiastically leaps to her feet. It’s plain to see that she knows the topic and is eager to show off her knowledge.

Watching on, Concern’s Benson Thuku remarks, “This really enables children to learn in school more effectively, because it is a continuation of what they have learned at home… and what they learn in school is also reinforced at home.”