When disaster strikes, every minute counts, both in the immediate aftermath and the long term. Here’s how a humanitarian response unfolds, from long before an emergency hits to long after the news crews have left.

Emergency response is part of Concern’s DNA. Last year, we responded to 50 emergencies in 22 countries and reached 16.8 million people in the process.

No two crises are exactly alike: The emergencies we respond to range from hyper-local events you’ll likely never hear about, to some of the largest humanitarian crises in the world today. They may be natural disasters, man-made crises, or part of a larger, complex crisis. These factors change the specifics of a response, but the overall strategy and imperative remain the same.

Here’s a step-by-step look at how a humanitarian response works, from the first hours to the first months — and long after the headlines fade. You can also jump to…

- The first hours

- The first day

- The first week

- The next two weeks

- The one-month mark

- The six-month mark

- The one-year mark

- Year two and beyond

Before a crisis even hits…

“A good response is planned out before it happens,” says Kirk Prichard, Vice President of Programs at Concern Worldwide US.

Risks are often predictable where we work: Bangladesh’s annual monsoon season means a chance of floods. Yemen faces year-round threats of sandstorms. Haiti is located within a known hurricane belt and also sits on a fault line that resulted in the 2010 and 2021 earthquakes.

Many countries are also in the middle of protracted conflict, an ongoing emergency that can lead to other crises like inflation or hunger. In these contexts, there are also usually fewer resources for relief efforts.

Enter the emergency preparedness plan

Every humanitarian aid organization has some form of an emergency preparedness plan in every country it works. These plans take are comprehensive looks at the potential risks facing an area, both natural and man-made, and include factors like:

- Political stability

- Economic vulnerability

- Existing humanitarian challenges

- Conflict-related risks

- Environmental hazards

At Concern, we call these PEER plans, short for “Preparedness for Effective Emergency Response.” In addition to looking at the external factors, we look at our own capacity to respond, with a focus on geography (where we work), areas of programming (what we do), our own staff capacity, and the capacity of partners we work with in-country.

Additionally, we look at our own capacity to respond to these risks, in terms of where we work, what we do, our staff expertise, and what partners we work with in-country. Lastly, these plans outline a course of action for each predictable emergency.

These plans are also living and collaborative documents, ones we work on with input from the organizations we work with in a community. We update them regularly and do a lot of prep work, like staff trainings and procuring supplies, year-round.

The first hours of a humanitarian response

When an emergency strikes, the first thing we do is make sure that all of our staff and their families are safe. The majority of our country teams are nationals and are just as impacted by a disaster as the communities we work with.

From there, we work through our PEER plan. The advance prep work we do means we’re able to move quickly, efficiently, and smartly — even in the most extreme circumstances.

The first day: Assessing needs and community coordination

Measure twice, cut once: One of the first steps of a PEER plan is to determine whether we’re actually needed. Sometimes, especially if an emergency strikes in another region (or even another country), other organizations already working there are able to respond more effectively. Even in an area where we work, we may not be needed. Some factors we consider before launching a response include:

- How fatal the emergency is

- How many people it deprives of basic needs

- Whether a state of emergency is declared

- Whether the government makes an appeal for international assistance

Answering these questions forms the basis of what we call a rapid needs assessment. This objective, bird’s eye view of the emergency is a key first step. But, as Prichard notes, “it doesn’t need to be complex: ‘There’s an earthquake in Türkiye and Syria. It’s massive. Done.’”

The first week: Lifesaving aid

The specifics of humanitarian relief will look different from country to country, based on what’s needed and what areas of programming we focus on in each area. Based on our PEER plans, however, we often keep a certain amount of materials (like NFI kits, hygiene kits, water, shelter kits, or emergency food aid) close by to distribute as quickly as possible.

Getting supplies into a crisis zone can take more than a week, especially if airports and roads are closed. Sometimes we’re able to share supplies with larger organizations (like UNICEF or the UNHCR). Often, we also have to make a call between taking what’s available and waiting a bit longer for better materials to come in from abroad.

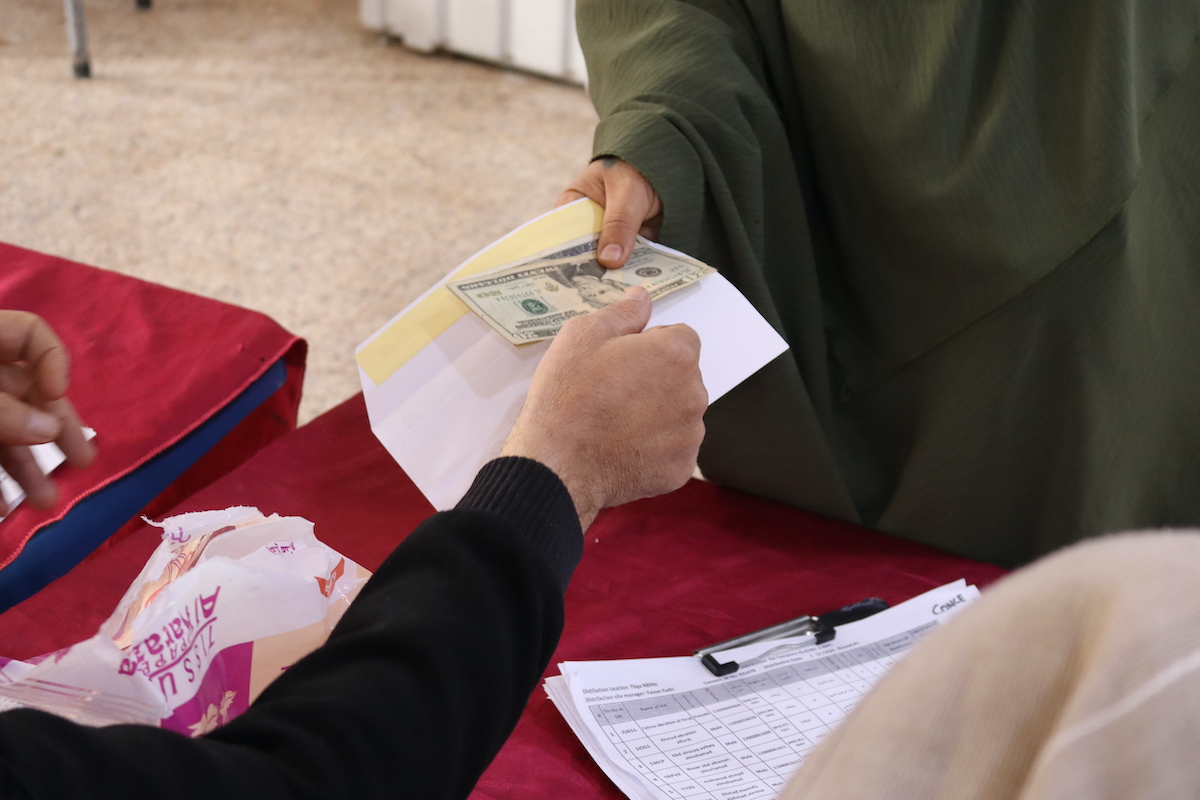

We call these initial distributions lifesaving aid — the sort of things you need to survive the first days or week of a disaster. But we also look beyond the main items: “You want to see if the markets are still functional, if there are things we can do locally to help the community,” adds Prichard. This is part of a larger shift within the humanitarian community of prioritizing cash transfers or vouchers over material aid whenever possible.

The benefits are many: Cash is easier to get into an area that may be affected by border closures or damaged roads. It allows people to prioritize their specific needs, and it helps keep economies stable during a major shock. However, there are also many instances in which supplies are depleted and we do need to bring them in from another region or country.

The next weeks: Frontline support — and a lot of behind-the-scenes action

Beyond distributions, we have other team members coordinating behind the scenes. Other Concern staff specialized in emergency response may travel in to help the initial recovery efforts. We also continually make sure our country teams have the training and emotional support they need.

During all of this, we also have team members focused on our finances. Emergencies are expensive, no matter how much you budget in advance. Sometimes our local banks are also affected by a disaster, so we have to make sure we can get funds from our accounts into the hands of the people we work with — whether as transfers, supplies, or support from our teams. For this reason, we have dedicated Emergency Funds with dedicated resources to help our teams respond quickly.

Support Concern’s Emergency Fund

All of this often happens amid ongoing challenges, like aftershocks following an earthquake or air-raid sirens and power outages (as has been the case with our response in Ukraine). We have teams monitoring security and weather reports as well, usually in partnership with other organizations.

The one-month mark: Delivering aid and keeping up with the goalposts

Our initial lifesaving assistance is usually distributed by the first month, ensuring that people have food, medical care, and shelter. However, “needs assessments are a continuous thing,” says Prichard. “The situation changes on a daily basis, and the needs are also changing. Even if you’re talking about displacement, people move constantly. The goalposts are always moving.”

While no two crises are the same, most humanitarian responses follow a predictable sequence: preparedness, assessment, lifesaving aid, recovery, and resilience.

Displacement presents its own challenges. If a person is displaced to another country, chances are likely that they’ll take some time to get settled in a host community, especially if they’re fleeing conflict. The crisis in Sudan led to massive overnight displacement in 2023, with thousands of Sudanese civilians crowding into transit sites in neighboring Chad. At the height of the rush, it took about two weeks to process asylum applications, letting people move on to a refugee camp.

The first month — and all of an emergency response, really — is about keeping up with those goalposts. But we don’t do it alone. We keep coordinating with our partners, including local NGOs, UN organizations, and both local and national governments to ensure that we’re able to get the right supplies and support to the people who need them most. The strongest responses that benefit everyone rely on both internal coordination and coordination within the sector.

The six-month mark: Beyond the frontlines

After frontline, lifesaving aid is distributed, we start to look beyond cash and kits. Water points and sanitation systems are often casualties of a humanitarian crisis. This can lead to a series of other risks like cholera, so repairing the damage and setting up temporary centers and latrines is a key step. It’s also an added bonus if we can incorporate a bit of disaster risk reduction into the process, say by earthquake-proofing systems.

Healthcare systems may also need more time to bounce back, especially if equipment has been damaged or clinics have been destroyed. If we’re responding to a crisis that involves displacement, we’ll also need to set up clinics around displacement sites (or mobile clinics that can travel between camps), as well as waterpoints and sanitation systems.

At the same time, frontline support often continues. We often distribute cash and vouchers over a period of three to six months — long enough for people to get back on their feet without creating a dependency. At a certain point, we may also pivot to cash-for-work and other livelihood programs to help with long-term recovery.

The one-year mark: Finding long-term recovery or a new normal

Depending on the scope of the emergency, a response can last for more than a year. In an age of complex humanitarian crises and protracted conflicts, this is sadly becoming the new normal.

If the crisis is acute (an event that had a set beginning and end), we start to focus on long-term recovery. Alongside this, we will still deliver essential supplies and kits past the six-month mark if needed — especially as seasons change and families living in displacement start to have different needs. Six months after the massive earthquake that hit Türkiye and Syria in 2023, we were still distributing NFI kits and hygiene kits to roughly 800 families a day.

“When organizations and the government started to respond to the emergency it brought hope but the conditions are still very hard,” said Ozge Celebi, Concern’s area manager in Adıyaman, six months after the earthquake. “Some people there are still living in tents, some of them have moved to containers.”

At this point in a response, as Celebi noted, “people feel overwhelmed. They want to move back to their routine, to their previous life, but it’s impossible to immediately change their living conditions, so they need some time to recover.”

This can be a frustrating moment, and one that we try to meet by helping families find a path to long-term recovery. In many cases, however, violence can become protracted and even natural disasters — like a drought — may not be fully done after the six-month mark. In these cases, we try to help families create a new normal as we continue to work with them towards recovery.

Throughout all of this, Concern continues to monitor our initiatives, changing approaches and areas of focus as needed, and working with communities, local partners, governments, and other organizations to deliver a coordinated response.

“People feel overwhelmed. They want to move back to their routine, to their previous life, but it’s impossible to immediately change their living conditions, so they need some time to recover.”

Year two and beyond: What comes next

Often at Concern we mark the one-year anniversary of a crisis to acknowledge the communities that have spent the last twelve months working towards recovery amid so much destruction — and our country teams who have spent the last twelve months working side-by-side with these communities. But that doesn’t mean the work is over.

Staying long after the news crews have left

“We are still working and the needs, they are still huge,” said Muhammed Kronfol, a Field Project Officer with Syria Relief at the one-year mark after the Türkiye-Syria earthquake.

In partnership with Concern, Syria Relief had spent the last 12 months supporting families living in mud-tracked displacement camps, now enduring a hot summer in tents. Muhamed, too, lost everything — including his house, his brother, and his sister-in-law. “But I am optimistic that the future will be better because we will not stop providing assistance until people can stand on their feet again,” he added.

One year after those earthquakes, Concern and Syria Relief were still distributing cash to Syrians — many already displaced by 12 years of conflict — affected by the earthquake.

Going where the need remains

In other cases, we may move in entirely different directions. Within our first year in Ukraine, we had found that the needs were shifting from different regions of the country, coalescing in eastern regions like Poltava, Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, and Donetsk. While providing families with cash payments to cover basic needs like food, rent and energy costs, we also moved into supporting collective centers and transit centers, working with large groups of Ukrainians moving away from the frontlines of conflict.

A new assessment in eastern Ukraine also showed that, for 95% of families, the conflict had left a number of psychological scars. We began focusing our response more on providing psychosocial support for people who had faced violence, fear, and loss. We delivered kits for children living in displacement sites that include items like coloring books, tea, cookies, and small games.

Psychologists also began leading sessions for older Ukrainians struggling with the psychological effects of war, as well as group sessions for children that include games, songs, and arts and crafts sessions. These go a long way towards bringing a sense of normalcy and community into a long-term crisis.

No set schedule, but key goals

These are often areas that we focus on earlier, when possible, but they’re key aspects of a humanitarian response after the first year, along with education (particularly when classrooms are closed or destroyed), and early economic recovery — ways that we can help families, even those still living through a crisis, to gain financial independence and begin to build or rebuild their personal safety nets.

Our clinics continue to treat patients (especially mothers-to-be and their young children), and where possible we look for ways to turn over programs to local partners once they can be run without our help.

Where possible, we also look for ways to build community resilience against future disasters. Our initial response to Cyclone Idai in Malawi and Mozambique, for example, included a focus on Climate Smart Agriculture. The 2019 storm had affected two harvests, destroying crops that were about to be picked and creating poor conditions for planting the next season’s harvest. CSA techniques, like fast-growing seeds, helped to offset those risks. Likewise, disaster risk reduction and community-based disaster risk management are other areas we focus on in regions that face similar known-unknowns.

When is an emergency response done?

That can be more complicated. Somalia, for example, has been locked in a cycle of crisis for several decades, as have many other countries where Concern works. In these cases, we often respond to more than one emergency at a time. We’re also in a period of crisis fatigue, which has led to many crises going underfunded or ignored. As needs go unmet, the impact of those losses gains compound interest, often deepening what is already a complex crisis.

In the best-case scenario, our emergency response isn’t needed after a few years, if not less. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, for example, the 2024-16 Ebola outbreak lasted about two years. By the beginning of 2017, however, we were able to transition from our Ebola response to other priorities in the country, like education and livelihoods.

Still, it depends on the nature of the crisis — an epidemic has a different timeframe than the recovery after an earthquake. But we can still get a lot done in a relatively short amount of time.

For example, Concern had left Nepal in 2010 after handing our projects over to local partners. We returned specifically to respond to the earthquake in 2015, which needed the support. We stayed in Nepal again for three years to take on some longer-term recovery and help to earthquake-proof five of the most underserved districts. Our initiatives created jobs that doubled incomes within the community, as well as doubled the improvement of and access to local sanitation facilities.

“No organization was willing to work in this place. We have many natural resources, but the only thing not in our favor is the remoteness and no access to good roads,” said one community leader in Gorkha. “Despite those circumstances, Concern Worldwide came here.”

Concern’s humanitarian and emergency response

Emergency response is part of Concern’s DNA. Last year alone, Concern responded to 50 emergencies in 22 countries, reaching 16.8 million people. Not each of these emergencies was a full humanitarian crisis, but many of them represent smaller shocks that set many people further and further behind in the middle of a larger crisis. In each context our goal remains the same: fulfill our humanitarian mandate.

When an emergency strikes, we seek out the most vulnerable and hardest-to-reach communities to meet their immediate needs, and work with them to design innovative, fast and effective responses. We stay with them to help rebuild their lives and to ensure that they are better able to cope with future crises. Your support allows us to do this vital work.